Teak is one of the most sought-after hardwoods in the world. A substantial amount is grown by smallholders in Latin America, Africa and Asia, who need help to improve production.

CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA) scientists James M. Roshetko and Aulia Perdana of the World Forestry Centre (ICRAF) Indonesia made a presentation on the range and complexities of teak farming by smallholders at the TEAKNET partner event during the 27th session of the Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission held in Colombo, Sri Lanka, on Oct. 23-27, 2017.

“Smallholders likely first became involved with growing teak from working on plantations,” explained Roshetko.

The famous taungya system was first established by the British in Myanmar (then Burma) in 1856 and then in Indonesia through to the 1880s. The system allowed farmers to grow annual crops in tree plantations while the trees were young. The weeding and fertilization helped the teak seedlings become well established and off-set establishment costs for the companies and farmers who also adopted the system on their own land.

As demand increased, smallholders’ teak plantations became common since the 1960s in many countries, including Bangladesh, Benin, Costa Rica, India, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Nigeria, Panama, Philippines, Solomon Islands, Thailand and Togo. Globally, there is a minimum 4.3 million hectares of teak plantations, 21 percent of which is managed by smallholders. Eighty-three percent of teak is grown in Asia, mainly in India, Indonesia and Myanmar.

Read more: Money grows on clove trees in Sulawesi

Smallholders’ teak in Indonesia

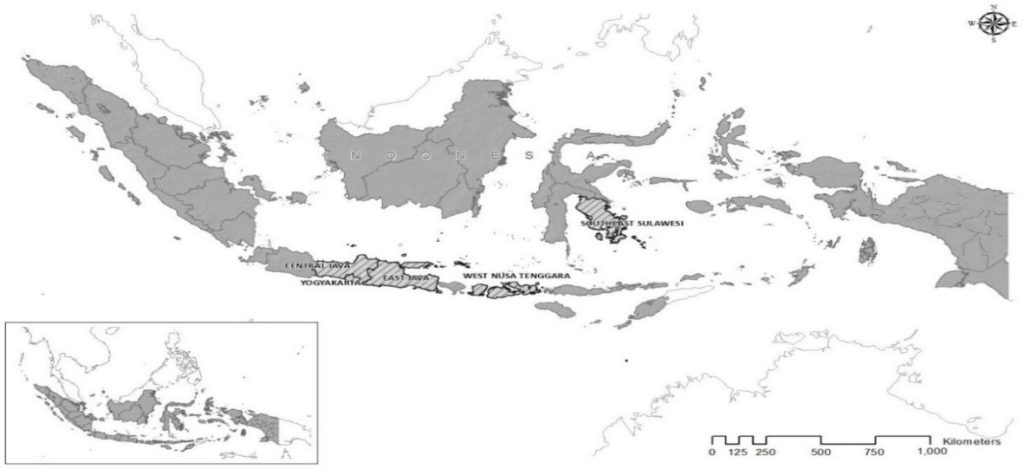

Approximately 1.5 million farm families grow teak on the island of Java in Indonesia. In the country as a whole, around 3.1 million hectares of farmland produce teak. Eighty percent (80 percent) of the teak logs used by small-to-medium-sized enterprises to produce furniture for domestic and international markets is grown by smallholders. In the provinces of Central and East Java in 2011, smallholders produced 14 times more timber (logs of all species) than the state-owned forestry company, 2,080,130 m3 compared to 146,420 m3, making them the dominant source of teak in Indonesia.

Indonesian farmers plant teak for a number of reasons. One of these is to serve as a long-term investment that constitutes family savings, like a living bank account. A tree is only harvested when funds are needed. According to Roshetko and Perdana’s research, a substantial percentage of smallholders (23 percent) claim they grow teak because it is part of their cultural heritage. Only 15 percent grow it to maximize market opportunities.

In Indonesia, most smallholders (managing 0.5-3 hectares; average 1 hectare) prefer farming systems that mix different species of trees, annual crops and livestock — rather than exclusively monocultural teak plantations — to spread risks, increase the diversity of products available for domestic use and sale, improve their surrounding environment and sustain traditional practices. In Central Java, farmers who grow teak usually devote 30-50 percent of their land to it, of which, perhaps 10 percent could be monocultural woodlots.

In Thailand and Lao PDR, smallholders also prefer mixed systems that enable off-farm opportunities, including temporary migration. In dry areas, such as Benin, Togo and Nigeria in Africa, teak competes with crops for land and labor yet smallholders seek to restore degraded land using teak. In Central and South America, farmers prefer monocultural teak plantations.

Read more: The role of agroforestry in climate-change adaptation in Southeast Asia

Farmers everywhere report that they know they need to improve their tree management skills, use higher quality seeds and seedlings, access better market information and expand their use of intercropping to make the land more productive. ICRAF promotes demonstration trials to help farmers improve their skills and gain technical knowledge in management of teak.

A trial typically features farmers volunteering the use of some of their land for research and training purposes. At the trial sites, farmers learn how to prepare a planting area, how to intercrop teak with annual crops, how to manage young trees, and how to thin and prune trees. They also learning how to establish tree nurseries to produce high-quality seedlings. The trials and nurseries serves as a learning center for neighboring farmers, who often replicate the model on their own land once they see success.

ICRAF also assists smallholders improve their marketing because usually a farmer simply produces the timber, which is taken from the farm by middlemen who sell it to other traders or directly to manufacturers. Smallholders who aggregate into cooperatives or other business entities typically enjoy higher prices.

Recommendations

According to Roshetko and Perdana, smallholders’ systems are not industrial teak plantations but rather more complex socioeconomic systems in which the use of trees as a living savings account is a valid approach. However, farmers need to improve their management. To do that, government and other support agencies can facilitate adoption of better silvicultural practices through well-informed extension and training, provision of practical manuals and news bulletins and through the wider use of farmers’ demonstration trials.

Specifically, the aim of improved management would be the production of larger diameter, better quality logs, which is what the markets want. Such knowledge stems from improved market positions by accessing information, developing links between teak farmers and industries, engaging in group marketing to decrease transaction costs, providing farmers with log grading and pricing systems that are used by the timber industry, and promoting more suitable and simplified government regulations that minimize transaction costs and make farm teak markets more efficient.

By Robert Finlayson, originally published at ICRAF’s Agroforestry World.

This work is linked to the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry. ICRAF is one of 15 members of the CGIAR, a global partnership for a food-secure future. We thank all donors who support research in development through their contributions to the CGIAR Fund.