We often think about man’s effect on the environment nowadays. We rarely stop to think about man’s effect on man.

Tracking the state of the world’s forests over the decades is, of course, extremely important, but what about the forest communities – are they also flourishing? Indeed, you could make a case that any forest hosting an impoverished community is a forest that, however flourishing today, tomorrow is destined for the ax. That is why, when an international team of social and environmental scientists got together to create a long term tropical forest monitoring project, they made sure to give it two arms of equal strength, the better to collect both environmental biophysical data and human socio-economic data.

By combining these two seams of data, researchers and policymakers are able to make long range predictions about effects in both directions. That is why this ambitious project is called Sentinel Landscapes.

Yves Laumonier, senior scientist at the Center for International Forestry Research, explains: “The Sentinel Landscapes are a long term research network to monitor not only biophysical data, but also social transformation in the landscape, especially for the livelihood of indigenous people and people who are still dependent on the forest.”

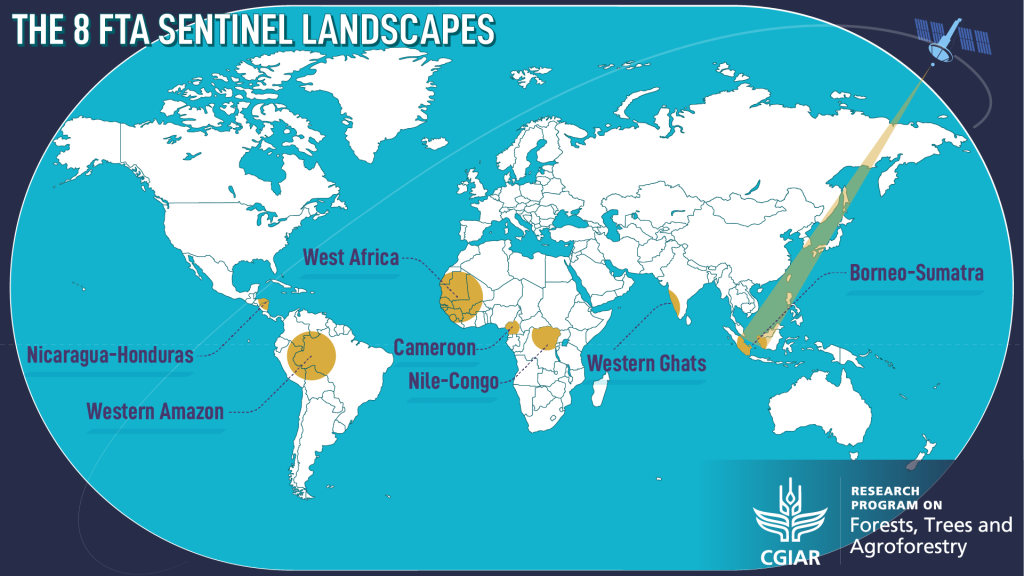

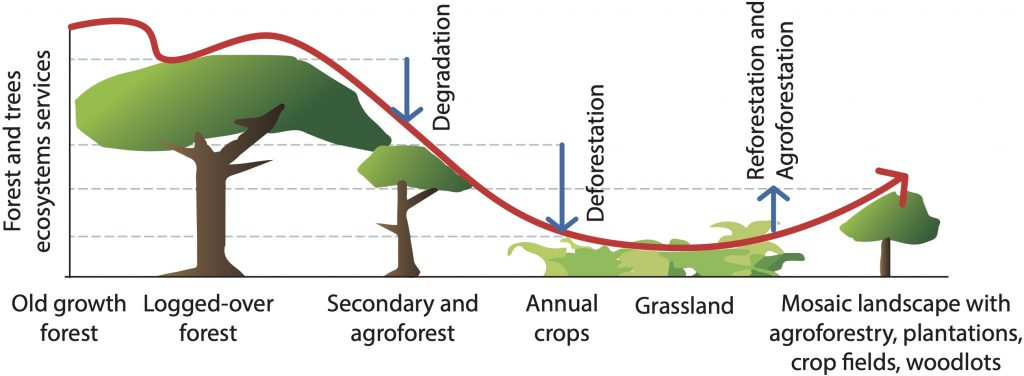

The Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA) research program of the CGIAR, led by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), has selected eight Sentinel Landscape research sites across the tropics, each site carefully chosen to represent different positions on the forest transition curve.

The forest transition curve describes how pristine primary forest is gradually cleared for timber, agriculture or development and how, at a certain point, this deforestation peaks and is replaced by the regrowth of secondary forest, planting of agroforestry or timber, leading to a degree of environmental recovery in the landscape.

With significant areas of standing ancient forest, the Heart of Borneo is perched at the top of the curve. But even here, crawling over the horizon, we see the tracks of bulldozers.

In Sentinel Solutions for the Anthropocene, we explored how long-term biophysical monitoring is a “global health check” for the tropics and how, in the Nicaragua-Honduras Sentinel Landscape, that data is being used to track forest degradation and climate change.

In this long read, we turn our attention to Borneo and look at how the different socio-economic contexts revealed by the Sentinel Landscape project affect forest conservation in one of the last forest frontiers.

Borneo: The Last Forest Frontier

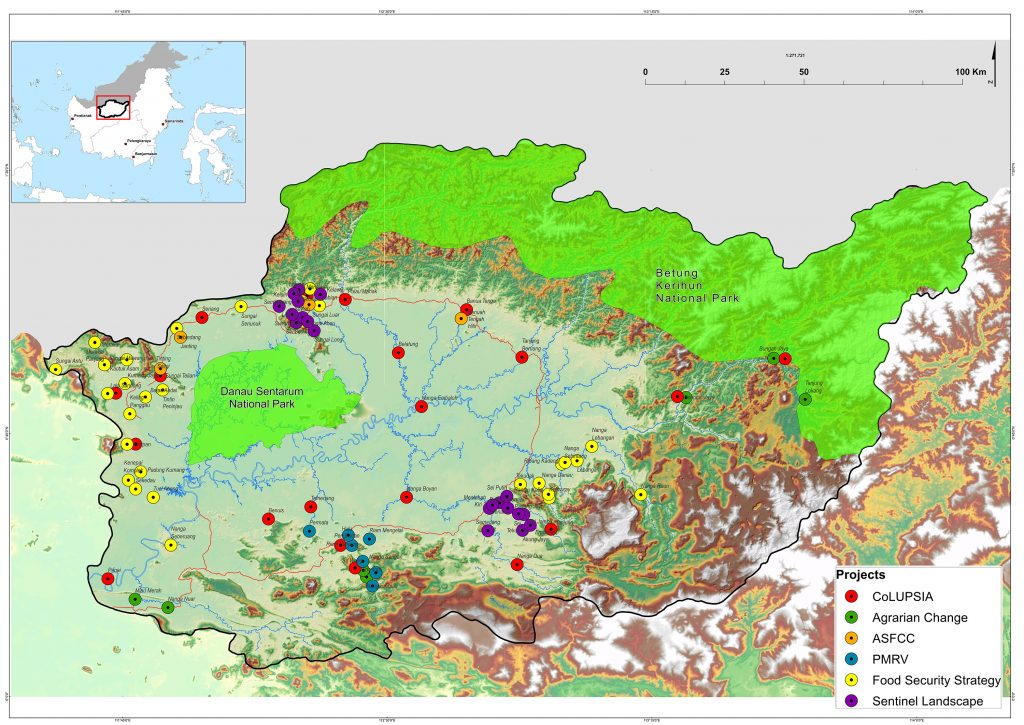

The recently published BSSL report focuses on two study blocks in the Kapuas Hulu Regency of West Kalimantan on Borneo. Straddling the equator, Borneo is the third largest island in the world, more than three times larger than Great Britain and seven times the size of Cuba. With 73 percent forest cover and two national parks, the report describes Kapuas Hulu as part of the “last forest frontier”.

READ MORE: The first Sentinel Landscape stocktaking pilot study: Report Nicaragua-Honduras

Yves Laumonier is lead author of the BSSL report. “We have other sites in Indonesia that are much more transformed or degraded,” he explains, “but we can imagine that Borneo shows the original state of the forest.”

However, Laumonier also warns that oil palm plantations are expanding near the biodiversity corridor between the two national parks, creating both economic opportunities and conflicts.

Lost without water

Between the two study blocks, Batang Lupar in the north and Mentebah in the south, lies the Danau Sentarum National Park: “a unique wetlands system with many lakes and swamp forests,” according to Laumonier. “Water fluctuation can be ten metres,” he continues. “During the rainy season some trees are underwater!”

The two sites were specifically chosen for their position as sentinels of the wetlands. As the report states: “Any transformation of these landscapes may have an impact on the integrity of the wetland ecosystem and on the communities living there.” This is significant because the wetlands are fed by the Kapuas River, the longest in Indonesia, sprawling over an area bigger than the countries of Costa Rica and Denmark put together.

The river is ecologically important, teeming with a rich diversity of fish, flora and fauna from the dense mountain rainforests to the alluvial delta where the Kapuas is swallowed by the South China Sea. But it is no less essential to human existence: a livelihood for fishermen and farmers, a shipping superhighway for passengers and freight, and a water reservoir that nourishes the whole of West Kalimantan province.

Indeed, the significance of the river to the people of Kapuas Hulu is not restricted to its magnitude, diversity or even the yield of its fruits. The indigenous Iban Dayak don’t navigate by the cardinal points – north, south, east or west – they navigate by reference to the natural world – uphill, downhill, upstream or downstream. The Iban are quite literally lost without water.

“We need this research”

Long term ecological monitoring projects aren’t new, but Sentinel Landscapes are the first to attempt such an undertaking in the tropics. “In Europe you have the Pan European Ecological Network, a large network of long term ecological research,” Laumonier says. “There is also something similar in the US. But in the tropics, it’s not existing.”

Given that tropical forests account for approximately half of the planet’s aboveground carbon and its critical importance for conserving the planet’s biodiversity, this is surprising, to say the least. “The key for me is to focus on the tropical belt,” Laumonier says. “We need this research. If you want to monitor climate change impact on the forest, and you don’t have long term data, it’s very difficult.”

However, long term monitoring projects in the tropics are not as straightforward as in the highly industrialized environments of Europe and North America. “Many ecological science methods used in Europe are not suitable for the tropics,” Laumonier says. “The tropics have the highest ecological biodiversity, and this makes monitoring much more complex than in Europe.”

Research in remote, pristine forests

It’s not only the scientific methods that need to be rewritten for the context. The practicalities of on site research are complicated too. “Pristine forests are only found nowadays in very remote areas that are difficult to access,” Laumonier says. “This is a burden on research. In Europe, you simply get in your car and go there.”

Even when the researchers reached the remote villages of Kapuas Hulu, that wasn’t the end of their challenges.

Alfa Simarangkir is a private consultant who helped collect the data from the socio-economic household surveys. “It took a long time to do the interviews in Batang Lupar especially,” she says. “Not many people speak Bahasa and they had difficulty understanding what we wanted to do.” Indeed, the BSSL report notes that, without a local partner who spoke the Iban dialect, the survey would have been impossible.

As well as the language barrier, Simarangkir and the rest of the team ran into trouble collecting even the most basic data, like the size of household land plots or what year a particular farm was opened. “We tend to use hectares, but in Batang Lupar they have their own local units and you can’t necessarily compare one unit with their neighbour’s,” Simarangkir says. “They also have difficulties remembering the precise timing of events. They don’t have that way of thinking. It took us one week to survey ten households!”

With 139 households to survey in Batang Lupar and another 300 in Mentebah, the socio-economic element of the Sentinel Landscape research was a heroic undertaking that compensated Laumonier, Simarangkir and their team with fascinating revelations.

The Iban Dayak of Batang Lupar: from headhunting to oil palm

“Borneo is one of the most forested of the Sentinel Landscape sites, so it’s a bit special,” Laumonier says. “But the local community of Batang Lupar are also quite special: the Iban Dayak.” The Iban are renowned as ferocious warriors, notorious for severing the heads of their enemies, smoking them over a fire and keeping them as grisly mementos – a practice, thankfully, long since ended.

They do still live in traditional longhouses, however. “These longhouses are not isolated individual houses, they are connected apartments, originally to protect themselves from the enemy,” Laumonier explains. “The shared longhouses mean that cohesion in the group is very high.”

The Iban, at least in Batang Lupar, also still live lives that “depend on the forest”, according to Laumonier. They practice swidden agriculture (also known as slash-and-burn or fire-fallow), clearing land for cultivation by cutting and burning the existing vegetation – mostly old fallows rather than primary forest.

But with intense international scrutiny of the annual Indonesian forest fires, this traditional farming method has become problematic. “To avoid excessive haze in the region, the Iban ancestral technique of using fire to clear their fields has recently been forbidden,” Laumonier says. “But the big fires you see in the news are never caused by the indigenous people: they know very well how to control their fires. The big fires you see every dry season are caused by the big industrial companies.”

Laumonier argues that the ban on swidden agriculture is based on an outdated theory of conservation. “In the 1980s, many governments and even conservationists wanted to get rid of agriculture in the forests,” he explains, “but now a lot of people think it’s not that bad, especially for biodiversity.”

“After one or two years of cultivation, the Iban leave the land fallow for regeneration,” Laumonier continues. “If the cycle is not too short – 10 or 15 years – the secondary forest has recovered and biodiversity is already very high.”

The light environmental touch of this traditional practice has a modern downside. “These people are living in subsistence,” Laumonier says. As development spreads even into the furthest reaches of Kapuas Hulu, traditional ways of living are being eroded by the temptation to cash in on the forest.

“The Iban plant rubber as a cash crop, but unfortunately the market price is very low and they can be tempted to shift to oil palm,” Laumonier says. “The oil palm companies are advancing little by little, sometimes with conflict, sometimes not,” he adds. “Many Iban are resisting the oil palm and in the peat swamps there’s a government-imposed moratorium on clearing – but it still happens.”

Mentebah: the road, the rubber and the gold

Batang Lupar and Mentebah are only 100km apart, but the local inhabitants could hardly live in more different situations.

“The tendency of some research is to work in one village and draw conclusions for whole region,” Laumonier says. “The advantage of the Sentinel Landscapes is that we get representative data for the larger region, such as districts.”

The most striking geographical difference between Batang Lupar and Mentebah districts is that, where Batang Lupar is relatively remote and hard to access, Mentebah lies on the main road between Sintang and the administrative capital of Kapuas Hulu, Putussibau. From this simple detail comes a cascade of socio-economic differences between the two sites. As Simarangkir says of Mentebah: “There is a really different way of living there. The road has given a huge opportunity to them.”

The road has also brought outsiders to the district. “In Mentebah, people from Java are given land by the government,” Simarangkir says. “The population is diverse compared to Batang Lupar.”

Simarangkir explains that the families in Batang Lupar depend more on natural resources, while those in Mentebah largely earn their living from other employment opportunities. In particular: tapping for rubber and mining for gold.

“The gold mining is illegal,” Simarangkir says. “When one of the respondents showed me some gold he had already made into a block, he told me that he would be in serious trouble with the police if they caught him.”

Despite the potentially lucrative gold industries, the socio-economic survey also discovered that there was significantly greater food insecurity in Mentebah, and that inequality was more extreme between the haves and the have-nots.

The curse of capitalism?

“In Mentebah you need money to buy your daily needs,” Simarangkir explains, “but in Batang Lupar I think they are lucky. They grow vegetables. If they need fish, they go to the river. If they need meat, the men go hunting. You don’t need money to buy food in Batang Lupar.”

The road is both a blessing and a curse for the people of Mentebah, as access to the markets of Sintang and Putussibau draws farmers away from their fields to the cash crops.

“Not many people in Mentebah concentrate on the productive landscape any more,” Simarangkir says. “Most of them work more on rubber plantations – but the rubber price fluctuates.” Without the guarantee of a stable price for rubber, a family’s fortunes in Mentebah can collapse from one year to the next in a way that the diversified subsistence farming of Batang Lupar would not.

The financial lure of rubber and gold means that the fields of Mentebah are less productive too. “In Mentebah, people might not have the time and labour to open fields because they are gold mining instead,” Simarangkir says. “In Batang Lupar they stay in the villages and have time to work in the fields.”

Despite their rice paddies, Simarangkir found that most households in Mentebah still have to buy rice. “They cannot predict the harvest,” she explains. “In Batang Lupar, one household can own many different land plots and they can rotate their crops. But in Mentebah they don’t rotate at all because they don’t have as much land. This is one reason why the harvest in Mentebah is not so good: you need to give time for the land to recover.”

Another striking difference between the two districts is that women own significantly more land in Batang Lupar than in Mentebah.

The women landowners of Batang Lupar

The BSSL socio-economic survey found the women owned nearly a third of all land plots in Batang Lupar, whereas women in Mentebah owned less than a fifth. Again, the road, rubber and gold of Mentebah offer clues to why this might be.

“Many of the women in the Batang Lupar come from the nearest village. In Mentebah, women come from cities all over Indonesia,” Simarangkir explains. This break in communal continuity and in the line of inheritance is one reason why women might own more land in Batang Lupar.

But Simarangkir speculates further: “I’m thinking that much of the land previously owned by women in Mentebah has already been sold because households can’t rely on unstable farm products like rubber,” she says. “Instead they rely on illegal gold mining. Sometimes they get a lot of money, but if not then they have to sell whatever they can – including, perhaps, their land.”

“There is a really different way of living there,” she says again.

The question is: how can the Sentinel Landscapes help the people of Kapuas Hulu navigate between these two different ways of life, between the equitable and ecologically sustainable subsistence farming of traditional Batang Lupar and the potentially lucrative market infrastructure of Mentebah?

Conservation or infrastructure: a false choice?

“At their best, Sentinel Landscapes give evidence to decision makers that something is going wrong with the environment,” Laumonier says. “For example, we can quickly see degradation of the forest because there are fewer and entirely different birds.”

“But,” Laumonier adds, “that evidence might not convince decision makers to change course because they – quite rightly – also want to develop and build hospitals and schools.”

It may seem that, with two national parks, Kapuas Hulu is environmentally well-protected, but it is not that straightforward.

“There are two national parks in Kapuas Hulu and that’s quite unique for Indonesia,” Laumonier explains. “Local authorities will say that they have been told to do this for conservation, but that the national parks are also the reason they have no money and no infrastructure.”

There has been a lot of international pressure on Indonesia to protect the forests of Borneo, with high profile campaigns, such as that to save the orangutan, driving the government to establish the national parks in Kapuas Hulu.

There are promising signs that Indonesian conservation efforts are being rewarded. Global Forest Watch recently reported that Indonesian primary forest loss in 2019 fell for the third consecutive year, despite a harrowing fire season. Deforestation is now 40 percent lower than the average annual loss between 2002 and 2016.

The same report indicates that conservation efforts have been even more successful in forests with protected status, bolstered by the announcement last year that the moratorium on forest clearing for palm plantations or logging will become permanent. According to 2016 figures from the Indonesian government, 49 percent of forests are protected in one way or another.

However, Laumonier suggests that choosing between the extremes of conservation and infrastructure is a false choice. “The solution is not always a national park,” Laumonier argues. “We can still do conservation with agroforestry and we can do more to connect the forest fragments. These measures may be as efficient as a national park.”

“In some places around the world, national parks aren’t working because the populations living next to the park are very poor and they don’t see the benefit of conservation,” Laumonier explains. “We have to find a trade-offs between conservation and development.”

Finding that balance isn’t easy – it would be impossible without environmental, cultural and socio-economic insights from the Sentinel Landscapes.

By David Charles. This article was produced by the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA). FTA is the world’s largest research for development program to enhance the role of forests, trees and agroforestry in sustainable development and food security and to address climate change. CIFOR leads FTA in partnership with Bioversity International, CATIE, CIRAD, INBAR, ICRAF and TBI. FTA’s work is supported by the CGIAR Trust Fund.