ICRAF’s global soil laboratory provides virtual training to India during the pandemic as part of the Land Degradation Surveillance Framework. This story is originally published on the World Agroforestry website

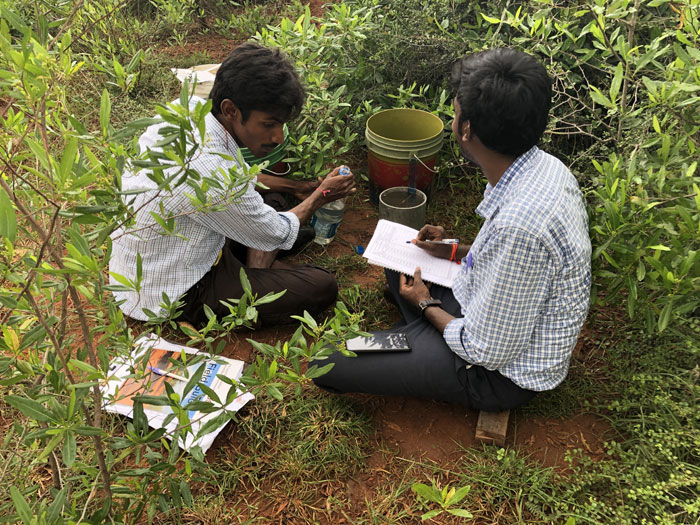

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, two organizations in India were implementing the Land Degradation Surveillance Framework (LDSF) in partnership with World Agroforestry (ICRAF), led by Tor-Gunnar Vågen, Leigh Winowiecki and Aida Tobella, to assess the health of land and soil across four states: Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Orissa and Rajasthan.

With the advent of the pandemic, planned training ground to a halt. But the work was considered too important to leave idle for long, so ICRAF’s Soil–Plant Spectral Diagnostic Laboratory carried out virtual training on soil processing on 2 July 2020. The two projects are funded by Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiatives, CGIAR Standing Panel on Impact Assessment, and the CGIAR research programs on Water, Land and Ecosystems, and Forests, Trees and Agroforestry.

In attendance virtually were 40 research coordinators, field officers, laboratory technicians and scientists from Rythu Sadhikara Samstha (Farmer’s Empowerment Organisation) and Foundation for Ecological Security, the two organizations with which ICRAF is collaborating.

‘The health of our planet’s soil is of huge importance,’ said Leigh Winoweicki, soil scientist and leader of the Soils Theme at ICRAF. ‘Many soils are degraded and becoming increasingly infertile. We urgently need to reverse this trend and the LDSF is an important part of the global effort. Training people around the world in how to assess ecosystem health, including soil health, using the LDSF is a key step. Not wanting to let the pandemic stop the work, we set up the virtual meeting to demonstrate the standard operating procedure for processing and air-drying soil samples collected using the LDSF method. We also wanted to answer any logistical questions on the processing of soil samples collected in the field. And, of course, keep the teams motivated!’

Training in India on laboratory soil analysis had already begun in Tirupati, 16–20 September 2019, with scientists from ICRAF engaging with 25 soil scientists, laboratory technicians and doctoral candidates. The training covered the fundamentals of mid-infrared spectroscopy (MIRS), built operational knowledge of the Alpha II Spectrometer, and expanded the trainees’ capacity in analysis of the mid-infrared spectra.

All soil samples were collected using the LDSF methodology, which was developed by ICRAF in response to the need for consistent field methods and indicator frameworks to assess ecosystem health.

This framework, which uses a hierarchical field sampling design, has been applied in projects across the global tropics and is currently one of the largest ecosystem-health databases in the world, with more than 40,000 observations. The LDSF includes measurements of key indicators of soil health, such as soil organic carbon and nutrients, as well as aboveground biodiversity measurements (for example, tree and shrub diversity) and land-degradation assessments of the prevalence of soil erosion.

‘When we assess land health, a nested hierarchical sampling design is useful as it allows us to conduct analyses that incorporate scale,’ explained Tor-Gunnar Vågen, who is a geoinformatics senior scientist at ICRAF and a pioneer of the LDSF method. ‘This is particularly important in predictive modeling where we need to understand uncertainty (or accuracy) of our models at different spatial scales.’

So far, Rythu Sadhikara Samstha has sampled six LDSF sites while the Foundation for Ecological Security has sampled over 2000 LDSF plots, totaling over 8000 soil samples ready to be processed.

‘It was a great experience for all of the Rythu Sadhikara Samstha science team to be part of the LDSF study,’ said Zakir Hussain, thematic lead of Climate Change and Livelihoods with Rythu Sadhikara Samstha. ‘The methodology and capacity-building process by Dr Leigh Winowiecki has been highly useful for our research coordinators, associates and natural farming fellows involved in the sampling. The training on MIRS has helped us to understand emerging technologies to monitor soil health across landscapes, at a scale relevant to farmers.’

All samples will be scanned using MIRS, a reliable, cost-efficient method for analyzing soil properties. The use of MIRS enables landscape-scale assessments of soil health, which was not possible when soil scientists relied only on traditional wet chemistry methods, which are time consuming and costly.

‘Even though there are several key elements to the successful application of MIRS,’ said Elvis Weullow, manager of ICRAF’s soils laboratory, ‘a critical one is the use of consistent sampling, processing and preparation protocols. This includes how the sample is dried, sieved, ground, sub-sampled and presented to the instrument.’

At the end of the training, there was a vibrant discussion between trainees and trainers on diverse issues, such as seeking clarification on some of the soil processing steps through packaging of processed samples to the storage of samples remaining after analysis.

‘We are thankful to the ICRAF team for organizing a very informative training for everyone involved in the collection of soil samples, their processing and subsampling,’ said Himani Sharma, program manager of the Foundation for Ecological Security. ‘It enabled all of us to follow the standard operating procedure to ensure the integrity of samples. We were inspired by the high precision lab where the samples will be analysed. We wish to have more sessions on the soil analysis process.’

In conclusion, while field surveys have slowed down due to COVID-19, following this virtual training, partners can start processing the soil samples locally.

Read also