The approval of India’s agroforestry policy in 2014 has been a first step in a global process supported by the FAO and the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). This year, for the first time, the Indian government has approved a budget for agroforestry of US$ 150 million. V.P. Singh, ICRAF’s Senior adviser for policy and impact has been the motor of the agroforestry success story in India. He is currently drafting a Working Paper that reflects on “Developing and Delivering Policy: An Experiential Process Learning in Developing the National Agroforestry Policy of India”. His work forms part of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry. We spoke to V.P. Singh at the sidelines of ICRAF’s Science Week in Nairobi 5-9 September 2016.

What are the biggest problems for agroforestry and for farmers who practice agroforestry in India?

Agroforestry or “Krishivaniki” had been practiced on the Indian subcontinent for a long time, , but it the business of the farmers alone. Politically, it was housed neither in agriculture nor in forestry, consequently as it lacked a supporting regulatory framework the farmers could not take out loans or insurance policies for agroforestry practices.

And, of course, extension services were not trained or equipped to support farmers who practice agroforestry on their land. There was no capacity building as needed.

But the biggest problem by far were the restrictions to tree-cutting and transit of timber that are enacted and enforced by the Ministry of Environment and Forests and Climate Change. Under these rules enacted to help protect forests, farmers were required to undertake a cumbersome process to obtain permits to cut trees even if they planted them, and even in areas absent of threats because there were no forests.

What was originally well-intentioned, to counter deforestation, became a major impediment for farmers who wanted to plant trees for timber values, as they were not allowed to fell them for any purpose.

How did ICRAF tackle these issues?

Around 2009 we started talking to the government and flagged that practicing agroforestry posed a problem. With support from the Indian government, we organized two national consultations one in 2011 and one in 2012. Based on these meetings, we were able to develop a rationale for agroforestry to be taken up in the form of a national policy for agroforestry. A policy is a living document, a wish list of the government, good at large for everyone.

After that, we started having consultations nearly every month. The main challenge was to engage different federal and state level ministries, and other agencies without their fighting over their competencies and justifications, pro or against having a policy . So we had to dialogue with them one at a time to get their input.

In those monthly meetings we gathered feedback first from the union government, then from the states, industry, financial institutions, international organizations, farmer groups and last but not the least from the civil society community. You get everyone’s concerns but you avoid them fighting face to face. And it worked, it worked very well.

How did you make the government see that they needed an agroforestry policy?

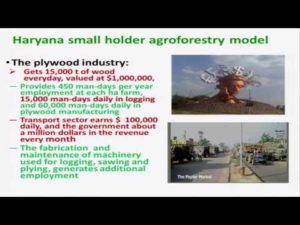

In every meeting I gave a presentation on what are the benefits of agroforestry, many endorsed by hard numbers. I reminded them that 62 percent of India’s timber requirements are met from the farms, US$ 24-30 billion in monetary terms. And there are also crops grown on the farms, which is additional. I made them see this as an economic issue. This is more than a 40-billion-dollar economy, and mostly from smallholder farms.

If the timber isn’t produced on farms, it has to be imported: 20 percent of the timber used in India is imported. We are talking about US$ 8 to 10 billion every year.

I also reinforced the notion that agroforestry can be practiced at a very small scale, by the marginalized smallholder, and at a very big scale, as well as in various designs and combinations in all ecological and socio-economic settings in the country. I presented evidence in the form of case profiles.

And, after a steady information sharing process in nine meetings over eight months, everyone agreed.

Everyone agreed, but where is the agroforestry policy?

In 2013, we formed an agroforestry policy drafting committee that set out to come up with a first draft. Feedback was collected from everyone concerned through electronic media, in hardcopy, even over the telephone. This feedback was incorporated into a second draft and when that was ready, we invited 100 stakeholders to a meeting to finalize.

We sat in a big room for 12 hours until everyone agreed on the final version, which was then sent to the cabinet and after its approval from the cabinet India’s first Agroforestry Policy was laid to both the houses of the parliament in 2014. We made sure to include deliverables and pathways to these deliverables. So the agroforestry policy is the only government policy in India that actually has clear deliverables and pathways.

So ICRAF facilitated the process and that was it?

We were able to very significantly influence the actions in the government and we are still involved because the government created an inter-ministerial committee to oversee the implementation of the policy, in which ICRAF is a permanent invitee member. Right now, I hold this position. ICRAF is also an official implementing partner and can support states in their development projects. We are also involved in capacity building on state level. We were able to successfully promote the cause of agroforestry because we didn’t impose anything on the government; it was a completely consultative process.

Two years have gone by. Are you satisfied with the progress in policy implementation?

Absolutely. This year, the government has for the first time approved an Agroforestry Mission, and budgeted US$ 150 million nationally to boost agroforestry. This money is 60 % of the total fund as 40% additional funds will be made leveraged from the state finances, and that will make about US $ 210 million. The money will specifically go to those states that follow the policy’s guidance to relax the tree felling and transit regulations for selected tree species in the respective states. We suggested that they start by freeing at least 20 species from these regulations. This made it easier for them to accept the policy.

Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana and Chhattisgarh have already exempted between 20-84 species from the felling and transit restriction.

Currently, each state can come up with a proposal of how they will use the “Mission money” for agroforestry in order to benefit from it. Which agroforestry system do they want to scale up? Who will be the main beneficiaries? And the inter-ministerial committee will scrutinize the proposals and decide where to put the money.

Thus, it will automatically benefit smallholders because smallholders and marginal holders make up about 85 percent of all farmers in India.

But the greatest impact in my view is the fact that agroforestry is now a distinctly recognized pathway in agriculture. New investments are made and institutions are upgraded. For example we now have a Central Agroforestry Research Institute with proper staff positions and budgets.

The policy drives the government’s command to have trees on every farm, and the progress we have already made in agroforestry would not have been possible without the policy.