Despite the high level of political engagement and the wide range of organizations involved in restoration projects from local to global levels, beyond some success stories, restoration is not happening at scale. Research is urgently needed to design, develop and upscale successful restoration approaches. As part of this effort, FTA, PIM and WLE publish a synthesis of a survey of CGIAR’s projects on restoration.

Forest and landscape restoration (FLR) have gained traction on the political agenda over the past decades with the multiplication of pledges and commitments on restoration such as the Bonn Challenge (2011), the New York Declaration on Forests (2014) and other global or regional initiatives. On March 1st, 2019, the United Nations General Assembly declared 2021-2030 the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (Resolution A/RES/73/284).

This UN Decade could offer unprecedented opportunities to address food security, job creation and climate change simultaneously. The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) considers that restoring 350 million hectares (ha) of degraded land by 2030, as committed in the New York Declaration on Forests, could generate USD 9 trillion in various ecosystem services and remove about 13–26 gigatons of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

However, despite the high level of political engagement and the wide range of institutions (public, private or civil society; local to global) involved in restoration projects, and beyond some success stories, restoration is not happening at scale.

In 2018, starting with a joint workshop, three CGIAR Research Programs (CRPs) – Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA); Policies, Institutions and Markets (PIM) and Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE) – decided to strengthen their collaboration to address this issue by bringing together different research streams working on soil, water and forest restoration.

“There are huge opportunities in bringing the three CRPs together to work on land restoration. Each of these CRPs works on different aspects of land restoration. Pooling this evidence in a user-friendly and accessible manner holds great potential for scaling, and for delivering enhanced impact from our CGIAR research” said Vincent Gitz, Izabella Koziell and Frank Place, the three CRP directors.

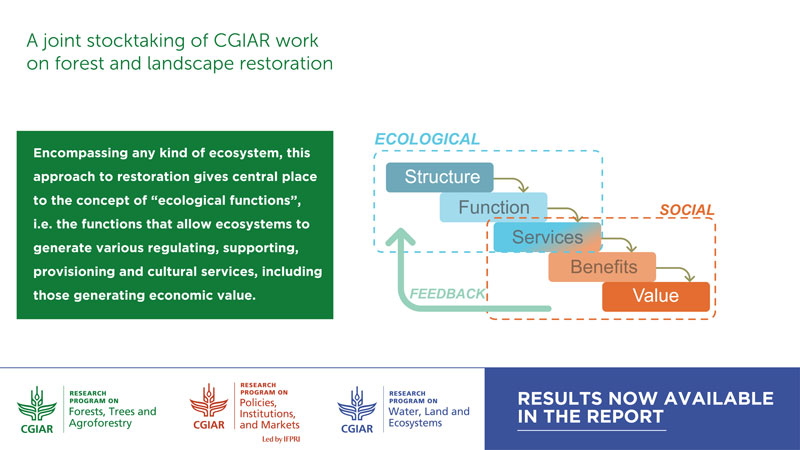

The three CRPs agreed on a broad scope of restoration, focused on the restoration of “ecological functions”, with the following definitions:

Degradation: Loss of functionality of e.g. land or forests, usually from a specific human perspective, based on change in land cover with consequences for ecosystem services

Restoration: Efforts to halt ongoing and reverse past degradation, by aiming for increased functionality (not necessarily recovering past system states).

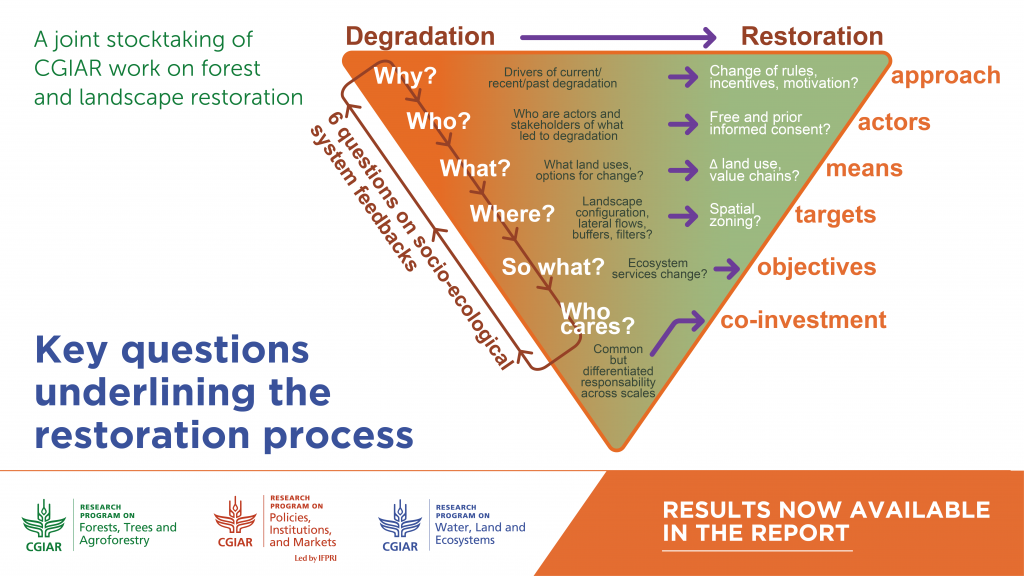

They also discussed theories of [induced] changes underlying landscape dynamics of degradation and restoration. The following questions helped structure the discussions:

- Why? What are the final goals of restoration efforts, which sustainable development goals can they contribute to?

- What? What are the drivers of degradation that need to be addressed? What are the ecological functions to be restored?

- Who? Who cares? Who are the stakeholders responsible for or impacted by land degradation? How stakeholders are encouraged, empowered and organized to act for forest and landscape restoration?

- How? How to design effective restoration interventions? What are the land use and land management options for change in different contexts, across countries and biomes?

- Where and when? How to operationalize action recognizing the connectivity across different spatial and temporal scales in the restoration process, considering the landscape’s spatial configuration and temporal dynamics?

As a first step of their collaboration, the 3 CRPs (FTA, PIM, WLE) conducted a broad survey of the CGIAR’s work on restoration, inviting contributions from other CRPs. The document published today is a synthesis of the survey results. The full database with full details on each initiative is available as an annex.

The survey reflects the implication of different CGIAR Centers (ICRAF, Bioversity, CIFOR, CIAT, IWMI, ILRI, ICRISAT, CIMMYT and IFPRI) in restoration projects across the tropics and sub-tropics, in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Some countries, such as Ethiopia, Kenya, Peru, or Indonesia concentrate many projects and provide strong opportunities for further collaboration among the three CRPs.

The survey shows the wide range of restoration activities undertaken by CGIAR CRPs and Centers, with their partners, from knowledge generation, methods, planning, modelling, assessment and evaluation, monitoring and mapping, to action on the ground. CGIAR restoration work can be divided into three broad categories: (1) case studies and projects; (2) tools for development; (3) approaches and conceptual frameworks.

The first category gathers case studies and projects comprising an element of field research. It comprises experimental plots, trials, local capacity building and implementation, on-the-ground assessments and surveys at different scales. It distinguishes: (i) “restoration-focused projects” where forest and land degradation is the main entry point and restoration is the main objective; from, (ii) “restoration-related projects” that can contribute to forest and landscape restoration while following other objectives (such as sustainable intensification or climate-smart agriculture). Half of the “restoration-focused” projects aim at assessing restoration practices with the view to upscale successful restoration experiences, such as the Ngitili fodder management system which contributed to the restoration of up to 270,000 ha over about 25 years in Shinyanga region, Tanzania. The others focus on climate change and climate-smart restoration, or on desertification and sand fixation. Six projects in this category focus on genetic diversity and on the performance and organization of the seed supply system, identified in this survey as a critical factor of success for restoration interventions. “Restoration-related projects” focus on various topics closely linked to restoration, including: sustainable land and water management; climate-smart agriculture; land tenure security and land governance reform; participatory governance and planning and collective farming.

The second category regroups: (i) tools, methods and guidelines, directed at decision makers or restoration practitioners at different levels, to support decision making; as well as, (ii) maps and models, measuring at different scales the intensity of degradation (i.e. efforts needed for restoration) or modeling the impacts of different land-use changes or land management practices. Models and maps often serve as the first layer for decision-making supporting tools. This category includes for instance two entries on the Land Degradation Surveillance Framework (LDSF), developed by ICRAF and applied, since 2005, in over 250 landscapes (100 km2 sites) across more than 30 countries. Using indicators such as vegetation cover, structure and floristic compositions, tree and shrub biodiversity, historic land use, visible signs of land degradation, and physical and chemical characteristics of soil (including soil organic carbon content and infiltration capacity), the LDSF, applicable to any landscape, provides a field protocol for assessing soil and ecosystem health to help decision makers to prioritize, monitor and track restoration interventions.

The third category, covering more theoretical work, includes: (i) evaluations, conceptual or theoretical frameworks around restoration and related issues; and (ii) systematic literature and/or project reviews, as well as meta-analyses on different topics linked to restoration. For instance a global survey on seed sourcing practices for restoration, was realized between 2015 and 2017 by Bioversity International, reviewing 136 restoration projects across 57 countries, and suggesting a typology of tree seed sourcing practices and their impact on restoration outcomes (Jalonen et al., 2018).

The survey describes projects operating at the landscape level or across multiple scales. This shows the importance of the landscape level to effectively combine integrated perspectives that allow synergies among different ecosystem components and functions with a deep knowledge of, and a fine adaptation to, local conditions. While many projects focus on the technical performance of restoration projects, relatively few investigate the economics, cost and benefits, of restoration and few examine their underlying power structures and power dynamics/games. This relative paucity of costs and benefit data has been noted by other organizations, an aspect that led to the launch of the FAO-led TEER initiative, to which FTA and several CGIAR centers contribute.

All the answers taken together provide useful insights for future restoration activities. In particular, they identify five critical factors of success for restoration interventions:

- secure tenure and use rights;

- access to markets (for inputs and outputs) and services;

- access to information, knowledge and know-how associated with sustainable and locally adapted land use and land management practices;

- awareness of the status of local ecosystem services, often used as a baseline to assess the level of degradation; and

- (v) high potential for restoration to contribute to global ecosystem services and attract international donors.

This synthesis will inform future work of FTA, PIM and WLE. It can also be used to support the design of restoration activities, programs and projects. Finally, it also illustrates with concrete examples the powerful contribution of forest and landscape restoration to the achievement of many, if not all of the 17 sustainable development goals. In particular, forest and landscape restoration, through the recovery of a range of ecological functions, can contribute to:

- enhance food security through the improvement of the ecosystem services sustaining agriculture at landscape scale

- improve natural resource use efficiency, thus reducing the pressure on the remaining natural habitats and addressing water scarcity;

- favour social justice by securing a more equitable access to natural resources (e.g. land, water and genetic resources), and a wider participation in decision-making processes, in particular for women and marginalized people; and,

- strengthen ecosystem, landscape and livelihoods resilience to economic shocks and natural disasters in a context of climate change.

The COVID 19 crisis has shown the importance of healthy ecosystems for healthy and resilient economies and societies. We hope that this document will contribute to integrate restoration as part of the efforts to “build back better” after the crisis.

This article was produced by the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA). FTA is the world’s largest research for development program to enhance the role of forests, trees and agroforestry in sustainable development and food security and to address climate change. CIFOR leads FTA in partnership with Bioversity International, CATIE, CIRAD, INBAR, ICRAF and TBI. FTA’s work is supported by the CGIAR Trust Fund.