Scientists hope a new interactive atlas that tracks deforestation annually will enable local governments to plan for change and avert widespread destruction of the forests on which indigenous people depend for food and livelihoods.

Due to its remote location and sparse population, Papua, Indonesia, harbors one of the Pacific’s last remaining expanses of pristine tropical forest. However, recent spikes in deforestation rates, accompanied by the expansion of industrial oil palm plantations, are signs that rapid change is on the horizon.

“The Papua Atlas will show where forest is being cleared on the island and who is responsible for the deforestation,” said David Gaveau, a research associate with the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), who demonstrated a prototype of the atlas at the International Conference on Biodiversity, Ecotourism and Creative Economy (ICBE) in Manokwari, Papua, on Oct. 7 to 11, 2018.

The platform, due to launch in mid-2019, will track deforestation on a monthly basis over the long-term.

Local government officials in charge of spatial planning welcome the development of the atlas, which they can use to help plan land use as the local population grows and demand for roads and other services increases in tandem. For example, the annual data provided by the atlas will provide insight into the dynamics of forest loss and the expansion of industrial oil palm concessions, and roads into forested areas.

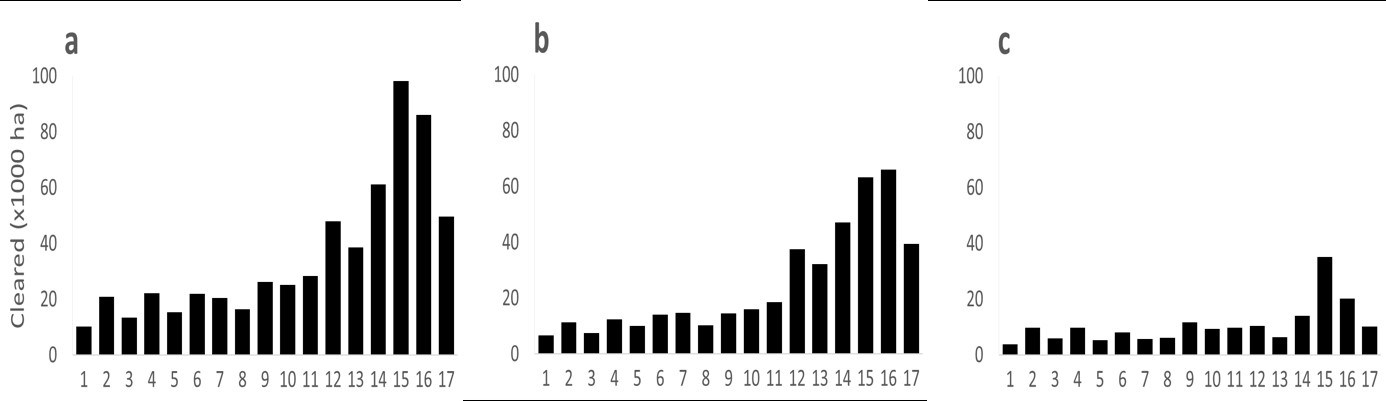

Old-growth forest in Indonesian Papua shrank by 2 percent, a loss of 600,000 hectares, between 2000 and 2017 (Fig. 1).

Annual forest loss in Indonesian Papua has accelerated gradually since 2000, reaching a peak in both provinces in 2015 and 2016, with 98,000 hectares and 85,000 hectares lost, respectively, before dropping markedly in 2017 (Fig. 1b & c).

Meanwhile, industrial plantations, mainly for oil palm, have nearly quadrupled since 2000, with the largest expansion in Papua province. Gaveau’s studies indicate that about 30 percent of all forest loss since 2000 has been due to clearing for industrial plantations.

“The island of New Guinea is perhaps the last large equatorial island that is still pristine,” Gaveau says. “It is still 90 percent natural forest, and it is sparsely populated.”

Because of its distance from key trading routes, Pacific ports and cities, it is expensive to install industrial facilities, such as palm oil refineries in Indonesian Papua. But the island is not immune to the spread of the palm oil industry, which has expanded throughout other islands, such as Borneo.

“As prime land becomes scarce on other islands, companies are turning their eyes to Papua,” Gaveau says.

That’s where the Papua Atlas comes in.

The interactive map is similar to the Atlas of Deforestation and Industrial Plantations in Borneo, also known as the Borneo Atlas, which Gaveau, a landscape ecologist, and Mohammad Agus Salim a Geographic Information Systems expert with CIFOR, developed to monitor deforestation on that island. The Borneo Atlas allows users to verify the location and ownership of more than 460 palm-oil mills on Borneo and monitor deforestation in the surrounding area.

Data about ownership show which companies linked to plantations are encroaching on forests and peat lands.

“The principle of the Papua Atlas is the same,” Gaveau says. “The overarching idea is to hold companies accountable for the deforestation they might have caused, whether or not it is done legally. The idea is that the Indonesian local and national governments can check those deforestation footprints in concessions to review the permits.”

See also: Atlas of deforestation and industrial plantations in Borneo

PLANNING FOR CHANGE

The arrival of industrial plantations is not the only change threatening to transform Papua’s pristine forest landscape. Logging for timber exports is increasing, tailings from a copper mine are destroying mangrove swamps, and people migrating from other islands are swelling urban populations.

As cities and towns expand, residents demand more public services, including better transportation. In planning everything from roads to housing, local government officials will have to assess the many tradeoffs that inevitably accompany development.

To ensure that the Papua Atlas is especially useful to land-use planners, Gaveau and Salim consulted extensively with local governments.

“New roads are being built to link the provinces of Papua and West Papua, and we know that with roads comes deforestation,” Salim says.

That could jeopardize the livelihoods of the indigenous people who live in the island’s forests and who depend on forest products for food, housing materials, fuel and their livelihoods.

Government officials are taking steps to put the brakes on some undesired impacts.

West Papua was declared a conservation province in October 2015. The government of West Papua has committed to keeping 70 percent of the province’s land under protection.

Only about half the province’s land is currently protected, so the challenge will be to increase that area.

In September 2018, Indonesian President Joko Widodo announced a three-year moratorium on new oil palm concessions on forest land managed by the national government, although the ban does not apply to forest within existing concessions or forest land controlled by local governments.

The Papua Atlas can help observers determine whether the moratorium is being respected, Gaveau says.

Government officials will also be able to use it to analyze land-use patterns and review licenses for agricultural concessions. Knowing which companies hold concessions and how they are using their land will enable government officials to adjust tax rates, Salim says.

“The atlas can be an important tool for conservation and land management,” he adds.

Read also: New map helps track palm-oil supply chains in Borneo

A LOCAL VIEW OF A GLOBAL

As the use of freely accessible platforms for tracking land use becomes more common, the Papua and Borneo atlases stand out for the degree of detail they offer.

Users can see which companies are clear-cutting old-growth forest, how much newly planted areas companies are adding, and where palm producers are moving into sensitive areas such as peat lands, which are crucial for carbon storage. The database also shows corporate relationships among companies, enabling users to better understand the market forces behind deforestation and to track corporations’ zero-deforestation commitments.

The atlas will provide a view of deforestation over time, with animations that show how plantations and roads have expanded, where land has been burned, where new land has been planted, and where forest and landscape restoration are under way.

“It’s important to be able to see both forest loss and the newly planted area, because you can then measure the conversion of forests to plantations,” Gaveau said “If forest was cleared and a plantation was established all within one year, there’s little question that both were the work of the company located in that place.”

The map can also be used to gauge impacts of those changes. When deforestation and planting occur near a river, for example, increased erosion is likely to affect aquatic life and ecosystems downstream.

Gaveau and Salim also hope it will solve a mystery. Deforestation on the island spiked in 2015 and 2016 even though no new concessions were granted in those years, which puzzles local government officials.

The interactive map can also link to platforms and databases developed locally, placing more useful information at the fingertips of local government officials.

“We are trying to develop ways of looking at the data that are important for analyzing impacts and planning for the future,” Gaveau said.

“These interactive platforms that promote corporate accountability and make it possible to trace products to their place of origin are just a start,” he added. “In a few years, we will have intelligent systems that will provide more detailed information, more frequently.”

Not only will that information provide a record of the past, but it will also give a glimpse of what lies ahead.

“Papua is important — it’s the last frontier of Indonesia, and one of the last in the tropical world,” Salim says. “The question is what do its people want for the future?”

The Papua Atlas will provide guideposts in the search for an answer.

By Barbara Fraser, originally published at CIFOR’s Forests News.

For more information, contact David Gaveau at D.Gaveau@cgiar.org and Mohammad Agus Salim at moh.agus.salim@gmail.com.

The Papua Atlas is being developed with financial assistance from Britain’s Department for International Development (DFID).

This research forms part of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry, which is supported by the CGIAR Trust Fund.