If it wasn’t for mankind chopping down trees, you get the sense that tropical rainforests around the world would be doing quite well.

According to the recent Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020 published by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, deforestation is decreasing – but is still an inconceivable 4.7M hectares per year. Global Forest Watch reports that in 2019 we lost enough tropical primary forest to cover an area nearly the size of Switzerland.

This is disastrous news – but it’s not like we humans are chopping down trees for fun. Yes, standing forests absorb our carbon emissions and regulate our weather – but for hundreds of millions of people around the world, felled forests are our factories and our farms.

Nowhere are the competing human needs to both expand and exploit forests more apparent than in the Congo Basin.

Sprawling over no fewer than ten countries in Central Africa, the Congo Basin is an almost unimaginably enormous area. It’s bigger than India. 80 million people depend on its woodlands and wetlands for their livelihoods. Imagine the entire population of Germany living in a forest: that’s the Congo Basin.

It’s a wonder that any trees are still standing in the Congo Basin at all. The pressure on these forests is immense, from supporting those growing local communities, to supplying timber and cocoa for national and international markets, while keeping up with the rapacious demand for the precious minerals buried deep in the soil: essential components for the device on which you’re reading this story.

Yet stand those trees must. A recent study published in Nature estimates that the Congo Basin rainforests absorb 370 million metric tons of the planet’s carbon emissions every year – making them a more important sequester of carbon than even the Amazon.

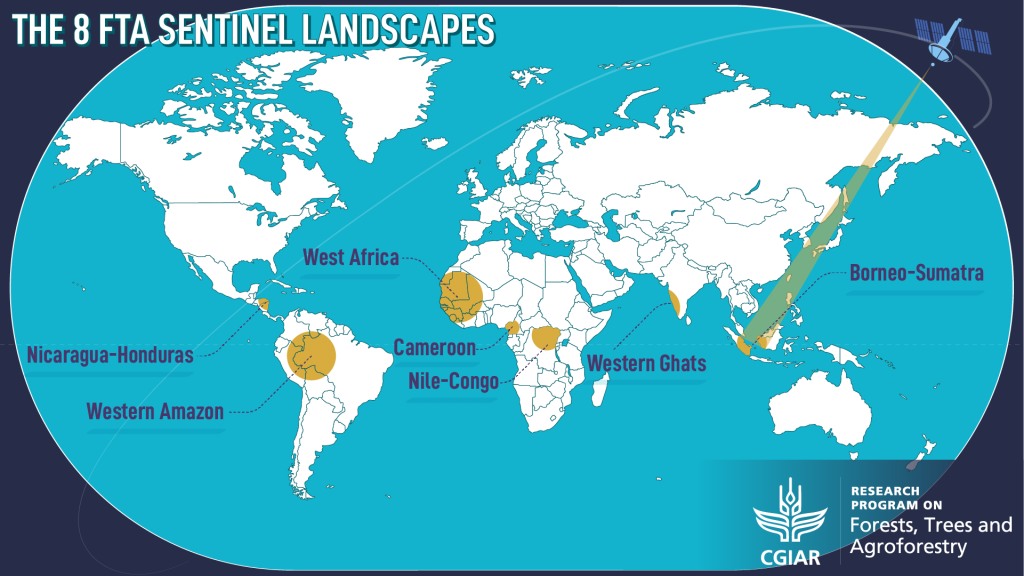

That’s why, when an international collaboration of scientists launched an urgent health check of the world’s forests, they made sure to come to the Congo Basin. The Congo Basin, with its ancient forests butting up against twenty-first century development, is the very definition of a Sentinel Landscape. The third for which the CGIAR Research program on Forests Trees and Agroforestry (FTA) has produced a report after a 10-year research, the other two being the Nicaragua-Honduras site and the Borneo site.

A closer look at the Congo Basin

Denis Sonwa was the coordinator of the CAFHUT Sentinel Landscape and lead author on the recently published stocktaking report: “The CAFHUT area was chosen to represent the different ecosystems and socioeconomic conditions in the Congo Basin in such a way that we can learn what are the drivers of deforestation, what forest models could be developed and what institutions could be useful as we develop responses to reduce/stop/reverse the anthropological ecology footprint on forest and natural ecosystems.”

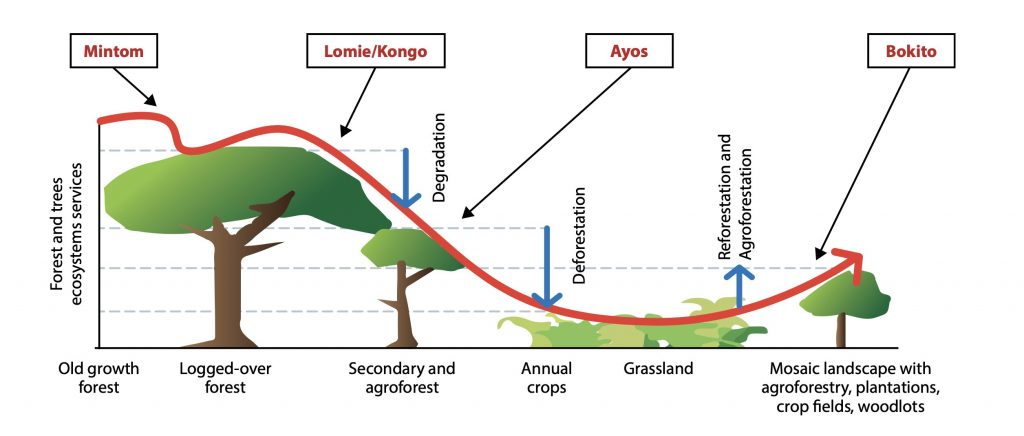

The four sentinel study sites were chosen to represent different points along the forest transition curve:

- Mintom: a transition zone between mature old growth forest and logged-over forest, with a mixture of forest concessions, including community forests, but also the largest expanse of undisturbed tropical rainforest in Cameroon. The opening of a major road in the area has brought access to markets and promises more radical change in the near future.

- Lomie-Kongo: an area composed of degraded mature forests, where concessions, community forestry and timber exploitation are influencing the forest structure. Lomie-Kongo is very sparsely populated and the inhabitants are primarily subsistence farmers without easy access to markets.

- Ayos: a more degraded peri-urban landscape, where vegetation is characterized by gallery forests surrounded by swamp forests of raffia. A well-established road network provides access to large markets and ensures economic investment in cocoa, coffee and oil palm plantations.

- Bokito: a forest-savanna or deforested landscape, where successful reforestation means farmers can grow cash and subsistence crops, including cocoa and oil palm. Good road access means that locals can sell their produce more profitably at larger markets.

From soil to satellite: Why Sentinel Landscapes matter

All eight of the world’s Sentinel Landscapes, from the Amazon to the Mekong, use the same underlying methodology. Land health data collection, for example, uses the respected Land Degradation Surveillance Framework and, in Cameroon, 1280 soil samples from 640 plots were taken and sent for analysis to the Soil-Plant Spectral Diagnostics Laboratory at World Agroforestry (ICRAF) in Nairobi, Kenya.

Socioeconomic information is gathered using a combination of primary and secondary research. This means boots on the ground: in the CAFHUT Sentinel Landscape, researchers held focus group discussions and surveyed 927 households in 38 villages across all four sites. The granularity and consistency of the research means that the results are comparable across the world and the data can be exploited by everyone from farmers to politicians.

Soil analyses and advances in tree domestication are evidently vital for individual farmers looking to increase yields of their cocoa plantations today. Meanwhile, socioeconomic research into the value chains of non-timber forest products (NTFP) and crops such as bush mango kola nuts or safou can help farmers diversify their income for tomorrow.

But the significance of the Sentinel Landscape goes far beyond the concerns of local farmers. “It’s a multi-strata system,” Sonwa says, “from the national arenas considerations down to the local realities. The Sentinel Landscapes project is a good opportunity to bring science and policy together. The data provides an overview of the situation before they can move ahead.”

Cameroon is signed up to the United Nations REDD+ programme, which pays governments for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. This funding is increasingly urgent. According to a 2020 study published in Nature, the world’s rainforests are absorbing less carbon than they were in the 1990s. Rising global temperatures and harsher and more frequent droughts hamper the forests’ carbon absorption capacity and, by 2030, the trees of the Congo will soak up 14 percent less carbon than they did in the early 2000s.

At a certain point – perhaps as soon as the next decade – our tropical forests could become carbon sources instead of sinks. At the moment, projections of the disastrous impact of climate breakdown are predicated on the world’s forests continuing to mop up our excess carbon emissions. If that assumption proves false, then… It’s fair to say that research like the Sentinel Landscapes becomes an existential necessity.

“The Congo rainforest is the most important on the African continent,” Sonwa adds, “so the Sentinel Landscape data is important for the international community as well.”

“Substantial contributions”

Peter Minang is Principal Science Advisor for the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and one of FTA’s Flagship leaders. He’s been working on the landscapes of the Congo Basin for 25 years.

“Although it was building on work we were already doing,” Minang says, “the CAFHUT Sentinel Landscape was about developing databases and learning whether we were making progress in the sites on a landscape scale. It was extremely important.”

Minang continues: “I think there is enough evidence in CAFHUT that our partners were able to make substantial contributions, collect data and advance knowledge and awareness – and to some extent make an impact on those landscapes.”

Ten years of CAFHUT research has identified three key land management issues in the Congo Basin:

- reducing deforestation and forest degradation;

- raising people out of poverty; and

- improving cocoa and other tree commodity agroforestry systems.

Poverty, as Denis Sonwa says, is one of the “key drivers” of deforestation. This means that any attempt to curb the logging rights of farmers and smallholders must simultaneously offer them an alternative livelihood.

At one of the sentinel sites, Bokito, the sustainable conversion of savanna grasslands to cocoa agroforestry helps resolve all three land management issues – at least partially.

Anything but timber: routes out of poverty

Bokito lies 150km from Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon. The landscape is forest-savanna or totally deforested. Poverty is a problem for local communities and contributes to drive deforestation, as farmers seek more fertile lands. Deforestation is itself a problem for local biodiversity as well as being one driver of the global catastrophe we all share: climate breakdown.

One of the problems with forests is that they aren’t directly profitable for local communities, whereas, as Peter Minang says, cutting down trees to plant cocoa is. “That automatically makes standing forests less competitive,” Minang says. “Outside timber, which is itself a forest degradation activity, there is a big question about how to make the forest directly productive.”

Aside from cocoa, one solution is for farmers to harvest non-timber forest products (NTFP), including fruit trees, nuts, medicinal plants and even insects such as maggots. But it’s not always easy to cash in on NTFPs as ICRAF scientist Divine Foundjem Tita explains: “Non-timber forest products are now more valuable for farmers, but the farmers are not always connected to the markets.”

That’s why, eight years ago, the CAFHUT partners helped link farmers to traders so that they could sell their NTFPs. The impact on communities has been “significant” according to Foundjem Tita, especially for women.

“During the school term, women take advantage to collect products and sell them,” Foundjem Tita says. “They can earn $100-1000 USD per year. This is significant.” In a country where GDP is only $3206 USD per capita, it certainly is.

“It’s about building connections, trust and relationships between collectors and traders,” Foundjem Tita says. “The money helps send their children to school, buy books for the kids—or participate in festivals like Christmas. It is very significant.”

Muscling in on ‘women’s cocoa’

As communities find alternative solutions, the economic landscape is changing. Historically, harvesting and selling NTFPs was women’s work. “They even call NTFPs ‘women’s cocoa’,” Foundjem Tita says. “But once the market starts increasing, more men start competing.”

Men are muscling in on the business. “Some men buy at a low price from women and sell high to traders,” Foundjem Tita says. “In one area, men now control 30 percent of the NTFP market.” As profitable as they have become, NTFPs will never be the whole solution. “They won’t completely eradicate poverty,” Foundjem Tita says. “But they will help farmers and have become a major income source for some.”

Nevertheless, Foundjem Tita believes that NTFPs could be more of a success story. In Cameroon, the sale of all forests products is regulated by a system of permits. These permits were designed to help preserve forests and regulate the supply of timber, but the authors of the report state that the procedures to obtain such permits for NTFPs are “complex, costly and beyond the capacity of most traders in agroforestry tree products, who are often operating at a small scale.”

“There are a lot of transaction costs in selling NTFPs, especially for communities who have to travel to the city,” Foundjem Tita says. “The consequences are high: it means that they end up selling locally without permits for a lower price.”

However, these legal roadblocks are well known and Foundjem Tita is optimistic that they will be corrected, as the government concludes its decade-long review of the law.

Driving deforestation

The most infamous causes of deforestation and forest degradation in the public imagination is logging, particularly illegal logging done without permits or accountability. But, as Peter Minang explains, it’s not so simple.

“Legal and illegal logging go together,” Minang says. “Once concessions are given, the people doing the logging don’t keep to the area where the legal concession was granted. A lot of the logging is not compliant with any traceability or accountability mechanism, so you have a lot of illegal logging.”

But the problem is not limited to logging companies overreaching their authorization. “Once a logging company opens the road,” Minang says, “illegal loggers can walk in with their chainsaws and take what they want. If there was no road, they wouldn’t have access.”

Illegal logging might loom large in the headlines, but Minang explains that the biggest driver of deforestation “by far” in the CAFHUT Sentinel Landscape is actually agriculture: cocoa, oil palm and, to some extent, rubber. Indeed, the stocktaking results found that the total area dedicated to the cultivation of palm oil is expected to double by 2030 compared to baseline of 2010. Meanwhile, cassava, groundnuts and maize were discovered to be the main drivers of cropland expansion.

This growth can only mean further deforestation. For example, the CoForTips project led by Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement (CIRAD) found that deforested areas in Mindourou and Guéfigué in the Bokito subdistrict are predicted to increase twofold over the next decade, compared to 2000–2010. And, recently, that deforestation is being pushed from a surprising direction.

Middle class guilt

Historically, there have been two types of agricultural foresters in the Congo Basin: local smallholders who manage 1-2 hectares for subsistence and national or international companies who open up 100 hectares of forest. But there’s a new game in town.

“In the last ten years, there has been a new trend of middle level local investors,” Minang says. “Imagine Peter sitting here realises that oil palm is good business. Instead of having 1-2 hectares as a local farmer, I come back as an elite and open up 20 hectares.”

These middle class investors have made their money in the city and club together to buy medium-sized plots of primary forest to turn into cocoa and oil palm plantations.

“If it was only smallholders, there wouldn’t be a problem,” Minang says. “They can’t expand too much: 1-2 hectares, maybe 3-4 hectares if you’re a really great family man,” he explains. “There is some evidence that this middle level is a growing driver of deforestation compared to the past.”

Power to the people

One obvious way to stop deforestation is to pay people to protect the forests. In conservation terms this is called ‘payment for ecosystem services’ and Cameroon has trialled carbon payments on a small scale.

“The pilot studies have had very mixed results,” Minang explains. “One of the big problems with payments is that they can dis-incentivize conservation in nearby places. Unless you do it at scale, payments can be counterproductive and this means that you can’t draw conclusions from pilot studies.”

But Minang is optimistic: “I think payments for ecosystem services is the future and it is important to scale up those payments to see whether they would actually work.”

One solution that has been tried at scale is community forestry. The 1994 Community Forest law was introduced in Cameroon to help local communities become financially sustainable while also conserving the forest.

“Community forestry is a key feature in this landscape,” Minang says. “It’s still thin, but there is some emerging evidence that community forestry can improve livelihoods and support the forests so that they are not susceptible to logging or intrusive farming.”

The benefits are clear. “Some communities have been able to get drinkable water,” Minang says. “Some are using the proceeds from community forestry to put roofs on schools, build football pitches and equip health centres.”

Help needed!

But community forestry isn’t working as well as it could be. Critics argue that most of these community forests are in secondary forests, which means that there isn’t much timber to be harvested and the community have to peddle in the much less profitable NTFPs – made even less profitable by the expenses of the permit system.

According to Peter Minang, communities need a lot more help. “On top of the list is improving the enterprise abilities of farmers: marketing, cooperatives and financing for the improvement of cocoa, food crops and NTFP – that’s one major part,” he says.

“The other part is the sustainable intensification and diversification of agriculture,” Minang continues. “Once you get farmers to produce more on a smaller piece of land, hypothetically you won’t get people clearing forest. People are clearing because they are going for more fertile lands.”

“The third part is enabling forest practise, making sure there are better policies for forest conservation, payments for ecosystem services and community-based management for forests. These are big areas for solutions to conservation of the landscape.”

The cocoa agroforestry solution?

Could cocoa agroforestry be the solution? As well as being a valuable cash crop, according to ICRAF’s Alternatives to Slash and Burn report, well managed cocoa plantations can maintain up to 60 percent of the carbon stock of primary forest. This is an improvement on the carbon capture of other food crops and represents hope for the heavily degraded savannah.

In a 2017 study published in Agroforestry, Denis Sonwa and his co-authors also found that the amount of carbon captured by cocoa agroforestry varies hugely depending on how the plantation is managed. For example: a cocoa plantation mixed with timber and NTFPs tree species stores more than twice the carbon of either an intensively-managed cocoa plantation, or even a cocoa plantation mixed with high densities of banana or plantain and oil palm.

Cocoa agroforestry is one of the dominant land uses throughout the Congo Basin. That means that advances in cultivation have the potential for huge knock-on benefits for both farmers and forests. Six projects in the CAFHUT Sentinel Landscape were focussed on improving cocoa agroforestry in terms of both yield and farmer incomes, while also reducing forest clearance for agriculture.

So are these projects delivering results for the three key land management issues in CAFHUT?

Peter Minang runs through his end of term report for the cocoa agroforestry interventions in Bokito: “Improving the livelihoods of the cocoa farmers by increasing cocoa productivity and helping communities in terms of NTFP? Excellent,” he says. “Reducing the carbon emissions of the cocoa farms? Of course – because of tree planting and the trees that are being kept.”

“However, we cannot 100 percent say that the project hasn’t increased deforestation in any way,” Minang concludes. “To get the results you want, you have to improve cocoa production and stop illegal logging. We think there is a weakness on the enforcement side.”

Two out of three ain’t bad?

Unfortunately, Bokito’s two out of three is about as good as it gets in the CAFHUT Sentinel Landscape. “I don’t think there are any places where they are getting it right,” Minang says. “Standards of living are still low and deforestation is increasing.”

“There has been some improvement in the productivity of cocoa, but because there are few alternative jobs in the city, people will always need to cut down trees to survive,” Minang continues. “I can guarantee you now with Covid-19 that there are people leaving the cities and going back to the countryside because there are more opportunities in the forests than in the city.”

Foundjem Tita agrees. “A more holistic approach needs to be developed to deal with deforestation and degradation, logging, cocoa agroforestry and other programmes like NTFPs.” he says. “In order to improve farmers’ livelihoods we will need a basket of solutions.”

Denis Sonwa is looking ahead to how the Sentinel Landscape data can be used for the good of both farmers and forests. “The information needs to be presented in a format that is understandable and digestible to those who are taking the decisions,” he says.

Despite the Congo Basin’s prominence as a global carbon sink, a 2019 CIFOR study found that over 2008–2017, Congo Basin forests received the least funding (USD 1.7 million) of the tropical zones, compared with the Amazon Basin (USD 5.1 million) and Southeast Asia (USD 8.1 million). There is scope and opportunity for donors to increase funding in the region: by mapping out the scale of the problems of poverty and deforestation in the cocoa-rich agroforestry of the Congo Basin, the data of the CAFHUT Sentinel Landscape can make a real difference by helping to source private funding for research.

“Take the chocolate companies, for example,” Sonwa says, “they’re now moving to what we call a zero deforested value chain.” Since 2017, investment from some of the world’s biggest chocolate and cocoa companies, including Mars, Guittard and Mondelēz, has been helping to fund both conservation and livelihoods in the forests of the Congo Basin.

It’s exactly this kind of international cooperation that our global forests need, as Denis Sonwa says: “from national arenas considerations down to the local realities”.

By David Charles. This article was produced by the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA). FTA is the world’s largest research for development program to enhance the role of forests, trees and agroforestry in sustainable development and food security and to address climate change. CIFOR leads FTA in partnership with ICRAF, The Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT, CATIE, CIRAD, INBAR and TBI. FTA’s work is supported by the CGIAR Trust Fund.