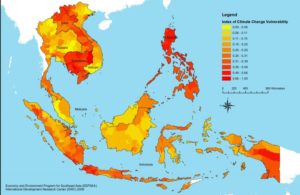

The ten countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations are highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Experts argue that agroforestry can help make the region’s millions of smallholding farmers more resilient and secure food supply.

Southeast Asia, with a population of more than 600 million mostly reliant on agriculture and forests, is ranked high on measures of vulnerability to the impact of climate change. The high-level Experts Dialogue on Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in ASEAN, held in Bali, Indonesia, 30 November 2016, heard that agroforestry could help farmers adapt while also mitigating climate change. The Dialogue was supported by Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

The list of impacts of climate change is long: shifting seasons that affect planting and growing periods; extreme heat, droughts, increased aridity and water shortages that reduce or wipe out yields; erratic rainfall that makes farm planning difficult if not impossible; storms, floods and landslides that destroy crops, livestock and homes; rising sea levels that salinate farm land; increased human, plant and livestock diseases; and lowered productivity of livestock, including fisheries.

‘Vulnerability is defined as the deficit in coping and adaptive capacity at household level’, explained Ingrid Öborn, Regional Coordinator for Southeast Asia for The World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF).

‘It is linked to buffering and filtering capacities at landscape and broader societal levels. Agroforestry is increasingly recognized as a sustainable land use in multifunctional landscapes that helps reduce farmers’ vulnerability and increase their ability to adapt, providing multiple benefits. As well as increasing carbon storage on formerly degraded or unused land, immediate benefits include increased and diversified food supply, increased income and maintenance of services provided by ecosystems, such as improved quantity and quality of water’.

Öborn pointed out that 30% of the world’s rural populations are already using trees and that trees are present on 46% of all agricultural land.

‘These “trees outside forests” are often not properly considered when governments make agricultural and forestry policies’, she said. ‘To address climate change thoroughly, we need to bring these trees to the forefront and support farmers to intensify and diversify their agroforests’.

ASEAN is one major body that has understood the need for an integrated perspective. Its Vision and Strategic Plan for ASEAN Cooperation in Food, Agriculture and Forestry 2016–2025, which was endorsed by the ASEAN ministers of agriculture and forestry in September 2015, takes a global and regional perspective and recognizes the main issues as 1) rapid economic growth; 2) regional integration and globalization; and 3) pressures on the natural resource base, including climate change.

The Strategy explicitly identifies agroforestry’s role in its plan of action: ‘Increase resilience to climate change, natural disasters and other shocks: expand resilient agroforestry systems where ecologically and economically appropriate’.

Öborn told the meeting that in the past, farmers often responded to climate variations by gradually changing their practices, mixing crops with trees to reduce risk if a crop failed because of weather patterns. Understanding this dynamism, replicating the most successful agroforestry systems and matching them to specific socio-cultural-ecological circumstances is crucial for helping farmers adapt to climate change. But governments also need to adapt to changing circumstances and think differently about how farmers, agriculture and forests interact.

She gave several examples of how agroforestry contributes to adaptation. In Viet Nam, researchers from ICRAF and partners found that ‘forest gardens’ sustain livelihoods when variable weather hits intensified crop cultivation. Farmers in Cam My in Central Viet Nam were using forests, as well as their farms, as gardens where they grew vegetables and trees for timber, fruit and other benefits. The gardens were established on land designated as State-owned forest. This created some conflict and highlighted the need to adjust policies to officially recognize farmers’ management that did not reduce the services provided by the forests.

Also in Viet Nam, in the Northwest, whole provinces were under monocultural maize farming on steeply sloping land that led to massive soil erosion, frequent landslides, loss of soil fertility, declining yields and overall severe degradation of the agro-ecosystem. The region was one of the poorest in the country.

Supported by the Australian Centre for Agricultural Research, ICRAF and national partners establishment experimental trials of agroforestry systems that had been computer-modeled to show that they could not only provide environmental benefits but also increase farmers’ incomes quickly. The trials were so successful that not only did neighbours adopt the systems but also the local governments in the three provinces established, together with farmers, three whole landscapes of agroforests of 50 hectares each.

More than 22,000 trees are being planted as well as 50,000 m of forage grasses along contour lines to reduce erosion, and 20,000 seedlings of five fruit-tree species. The landscapes are a co-investment by the ACIAR project (54%), farmers (35%) and the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (11%).

In Indonesia, an area in Central Java was heavily logged in the 1950s, resulting in soil erosion, agricultural decline, drought-induced famines and high levels of poverty. Re-agroforestation was undertaken, using teak trees as the major species. The landscape was rehabilitated successfully, moving from 2 to 28% tree cover, with teak making up over half. Farmers interviewed said they planted teak as a kind of ‘savings bank’ and because it was part of their cultural heritage.

Only 15% maximized teak management for sale to markets. Most farmers preferred mixed systems with diverse trees and crops that sustained customary life and improved the environment. Nevertheless, they said they also wanted to improve their management, obtain better-quality seeds and seedlings, have greater access to markets and expand the amount of intercropping between their trees.

Globally, smallholders produce 90% of cocoa, 75% of rubber, 67% of coffee, 40% of palm oil, 25% of tea and 20–30% of teak in an annual trade worth USD 60 billion. In Indonesia, smallholders are key producers of rubber, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, tea, tea, rattan, honey, sandalwood, damar, benzoin, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg and candlenut, most of which are produced in agroforestry systems that could benefit from improved management, greater technical knowledge and easier access to markets.

‘Economic value and potential yields depend on socioeconomic and biophysical conditions and farmers’ management practices’, said Öborn. ‘We need to understand farmers’ contexts and needs if we are to help improve their agroforests and thus their livelihoods and resilience to climate change’.

To help farmers adopt agroforestry or improve the management of the agroforests they already have, they need a range of support, such as helping increase their technical knowledge, providing them with accurate weather forecasts and advice on how specific agroforests that suit their conditions can buffer farms against climate change. Other barriers to adoption include a lack of secure land tenure and weak links between agroforestry and climate, food security and development policies.

‘It is a big challenge for governments to sort out all of this’, confirmed Öborn. ‘But the benefits are worth it and can be aggregated from individual farms to whole landscapes that can reap the rewards in the form of biodiversity conservation, better watershed management and carbon sequestration. Globally, agroforestry can be a substantial contribution to reducing greenhouse-gas emissions and helping ASEAN nations meet their Nationally Determined Contributions’.

To help governments understand the full range of benefits and challenges, ICRAF is releasing a series of policy briefs under the aegis of the ASEAN Working Group on Social Forestry. The first in the series, Agroforestry in Southeast Asia: bridging the forestry–agriculture divide for sustainable development, was launched during the Experts Dialogue.

Read the first four policy briefs

Van Noordwijk M, Lasco RD. 2016. Agroforestry in Southeast Asia: bridging the forestry-agriculture divide for sustainable development. Policy Brief no. 67. Agroforestry options for ASEAN series no. 1. Bogor, Indonesia: World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) Southeast Asia Regional Program; Jakarta, Indonesia: ASEAN-Swiss Partnership on Social Forestry and Climate Change.

De Royer S, Ratnamhin A, Wangpakapattanawong P. 2016. Swidden-fallow agroforestry for sustainable land use in Southeast Asia Countries. Policy Brief no. 68. Agroforestry options for ASEAN series no. 2. Bogor, Indonesia: World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) Southeast Asia Regional Program; Jakarta, Indonesia: ASEAN-Swiss Partnership on Social Forestry and Climate Change.

Hoan DT, Catacutan DC, Nguyen TH. 2016. Agroforestry for sustainable mountain management in Southeast Asia. Policy Brief no. 69. Agroforestry options for ASEAN series no. 3. Bogor, Indonesia: World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) Southeast Asia Regional Program; Jakarta, Indonesia: ASEAN-Swiss Partnership on Social Forestry and Climate Change.

Widayati A, Tata HL, van Noordwijk M. 2016. Agroforestry on peatlands: combining productive and protective functions as part of restoration. Policy Brief no. 70. Agroforestry options for ASEAN series no. 4. Bogor, Indonesia: World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) Southeast Asia Regional Program; Jakarta, Indonesia: ASEAN-Swiss Partnership on Social Forestry and Climate Change.