More assistance could help to support the Indonesian bamboo industry, which is currently seen as underdeveloped and missing out on opportunities.

Despite a significant contribution to the economy, the bamboo industry in Indonesia remains underdeveloped. In terms of policy, bamboo is also often overlooked, with timber receiving much more attention.

Indonesia is home to around 143 bamboo species and 2.1 million hectares of bamboo forest. For centuries, bamboo has been used for construction, housing, household items and handicrafts. It is a no-fuss species that grows rapidly compared to timber, is highly adaptable to various types of soils, and is relatively easy to process. The industry provides livelihoods for hundreds of thousands of people.

Marcellinus Utomo of the Australian National University has explored how the government of Indonesia could foster the bamboo industry, focusing on bamboo value chains in Gunung Kidul, Yogyakarta, as part of the Developing and Promoting Market-based Agroforestry Options and Integrated Landscape Management for Smallholder Forestry in Indonesia project, which is funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Development and also forms part of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA).

“The research findings are very valuable to us,” said project leader Aulia Perdana of the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). “It will help us devise interventions, such as bamboo agroforestry systems, extension programs for silviculture, ways to better process raw material, and improve marketing and business skills. Additionally, we plan to test how to increase the scale of bamboo agroforestry to support the Thousand Bamboo Villages program.”

Read more: Mapping bamboo forest resources in East Africa

In December 2015, the Indonesian government initiated a 10-year program called Seribu Desa Bambu (One thousand bamboo villages) to foster the industry by establishing bamboo forests and factories. Yet, according to the research, the results have been suboptimal.

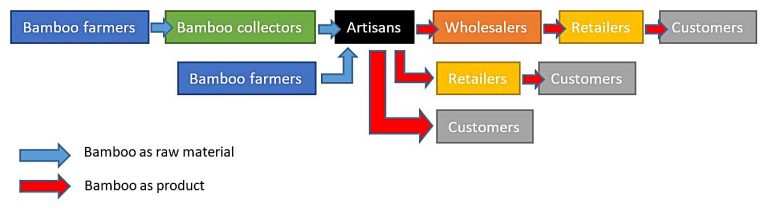

Utomo examined the value chains of three bamboo products: durable bamboo, kitchen utensils and handicrafts. Data were collected from June to August 2016 through interviews, focus groups, a literature review and direct observations.

He found that durable bamboo had the shortest chain with the least people involved, followed by kitchen utensils. The handicraft chain was the longest, involving the greatest number of people.

Although people in all the value chains were typically well-informed about markets, there was limited sharing of information by buyers to sellers about prices, which could be detrimental for some of those along the chain, such as growers and artisans.

Bamboo is still considered a cheap material. Straight bamboo with a large diameter can sell for between Rp 6,000 and Rp 7,000 (approximately 50 US cents) per pole. Because of the low prices, farmers are not inclined to go to great lengths, neither applying fertilizer nor using silvicultural techniques.

When income from bamboo was compared with national minimum income per capita, Utomo projected that for farmers the economic contribution of bamboo handicrafts was a mere 0.6–1 percent of the minimum income, while kitchen utensils contributed 6.4–8.9 percent and durable bamboo products 7.7–13.5 percent.

These low contributions were caused not only by low prices but also irregular demand. To make ends meet, farmers usually cultivated seasonal crops and rice and grew timber for savings.

Read more: Lack of knowledge may impede economic potential

Artisans who process and add value to bamboo, however, can gain significant income. Durable bamboo contributed 13.2–104 percent, to their incomes, kitchen utensils 152–472 percent, and handicrafts 169 percent up to 3,072 percent. From the numbers in the value chains, profit do not appear to be evenly distributed, with growers left as the most disadvantaged.

Some growers also lack knowledge about bamboo management, whereas artisans lack marketing knowledge and entrepreneurial skills. Weak English-language skills further constrain artisans’ opportunities because many buyers are foreigners.

Utomo also noted a lack of coordination between government bodies and limited coordination between people within value chains, which restricted overall growth of the industry. He suggested the government could establish a taskforce that would operate at both national and local levels to integrate the industry within agricultural and rural development programs, lobby ministries, collaborate with NGOs and research institutions, encourage more extension services, improve promotion of handicrafts, and support better access to microcredit. The formation of producer cooperatives, meanwhile, would help to build capacity and enhance bargaining positions within a chain.

By Enggar Paramita, originally published at ICRAF’s Agroforestry World.

This work is supported by the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry. We thank all donors who support research in development through their contributions to the CGIAR Fund.