The work on safeguarding these communities from further marginalisation and, indeed, bringing their concerns into mainstream political arenas, is rooted in the context of land grabs for mining, plantations and other commercial and state interests, which deprive indigenous people of their land and livelihoods.

According to Sébastien de Royer, Gamma Galudra and Ujjwal Pradhan, who were presenting at the World Agroforestry Centre’s annual Science Week in Nairobi, Kenya, their ambition is to integrate social safeguards into the land-use planning process in Indonesia, building on similar work carried out under reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation plus conservation (REDD+) schemes; through investment and certification schemes with the World Bank; REDD+ Social and Environmental Standards; Climate, Community and Biodiversity Standards; UN-REDD; Forest Stewardship Council; and the International Finance Corporation.

However, the team aims to go beyond mere compliance to integration into usual government practices and active support of rights. They intend to use sub-national arenas and the political and administrative context of land-use planning to experiment with the implementation of social safeguards involving a broad range of stakeholders in a real-time strategic negotiation that respects the rights and voices of local communities and indigenous people.

The team explained that social safeguards are essentially precautionary measures to protect local people from any infringement on their rights to land, natural resources, knowledge, culture, practices and all social attributes that are central for fulfilling their basic rights. The safeguards are a mix of principles, conditions, procedures and approaches that take into account rights and aspirations, which do not harm or undermine, but rather enhance, the rights of communities, indigenous people and others involved in a landscape, including rights holders and land users. The concept of ‘safeguards’ encompasses free, prior and informed consent; participation; land conflict; land and natural resources rights; livelihoods and food security; and poverty alleviation.

The legal foundation for safeguards rests on international human rights standards as enacted by the International Labor Organization’s Convention no. 169; the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People; Convention for the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination; the Convention on Biological Diversity’s article 8j on indigenous knowledge.

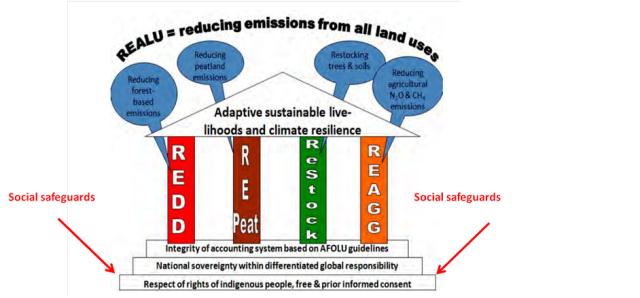

Within the context of reducing emissions from all land uses (REALU), indigenous people as managers of sustainable agricultural practices form the basic foundation of the ‘temple’ of principles and actions.

In this context, especially in Indonesia, much of the work around social safeguards is about land tenure since a lack of clarity over the right to land is often the source of conflict between local communities, governments and businesses. For example, in Jambi province on Sumatra Island, when timber and crop plantation companies have been granted concessions over major areas of a district, resistance from local communities who consider they have traditional right to the land is a common accompaniment.

Further, as well as the wholesale conversion of vast areas of traditionally managed forest, the concessions often involve the inward migration of workers from other parts of Indonesia who move into areas formerly under traditional control, changing local land-use norms and practices and stimulating further conflict and contested claims over land. These migrants act as intermediaries, reshaping the land-tenure system and shifting the balance of power between local communities, the state and business concessions.

In a dynamic situation such as this, if social safeguards had been integrated into land-use planning it would be very likely that conflict would have been much less, even though it would have undoubtedly been difficult to obtain free, prior and informed consent for any plans given the intense and complex interactions between the various groups. ‘Free, prior and informed consent’, which is often given the acronym FPIC, can be simply defined as protecting the right of local and indigenous communities to negotiate the terms of externally imposed, policies, programs, projects and activities.

The complexities of integrating social safeguards into governments’ land-use planning should not be underestimated. There are competing needs, interests and values; a lack of reliable information about social, economic and biophysical conditions; limited understanding of sustainable development; and a general lack of involvement by the people. Further hindrances include unresolved land tenure and resources conflicts; unclear traditional community rights; lack of integration of sectoral plans; little consideration of climate-change mitigation and adaptation; and weak technical planning skills.

However, the stakes are high, because the issues above have inevitably led to high greenhouse-gas emissions from the land-based sector in Indonesia; little consideration of the rights and aspirations of local and indigenous communities, with accompanying dispossession of traditionally owned and managed land; and a huge number of conflicts over land and resources that further restricts the social and economic development of the entire nation.

The team’s approach to overcome these obstacles is to set up a system that first understands local complexities and social realities; ensures the full participation of multiple stakeholders; protects rights, knowledge, skills, institutions and management systems; informs spatial and development plans; reconciles local claims and land rights and ensures they are included in planning; has a long-term, positive impact on livelihoods and social benefits; and maintains and enhances environmental services for social benefits.

In the Participatory Monitoring by Civil Society of Land-use Planning for Low-emissions Development Strategies (Parcimon) project, which is funded by the European Union, the team is working in the districts of Jayapura, Merauke and Jayawijaya. The province of Papua has over 200 distinct indigenous groups; the nation’s highest level of poverty (5%); high forest cover; and land grabbing for food estates and mining leading to violent conflict.

A recent decision by the constitutional court to return some state forestland to traditional control seems set to reduce the lack of clarity over rights but it is still unclear how the Government proposes to implement the ruling. In this environment, the team plans to undertake a four-phase process to achieve the goal of safeguarding community rights: preparation; interpretation; governance; and monitoring and evaluation.